Politics and sport: How FIFA, UEFA and the IOC regulate political statements by athletes

For sports fans in Europe, 2016 sees the latest instalment of the bi-annual collision of the Olympic and football calendars, with the hosting of the European Football Championship in France in June and July, followed by the Summer Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro in August. Granted, two very different events and audiences, but each event comes with its own profile and ability to appeal to large groups of people, elements which make them both a sponsor’s dream and a potential platform for the expression of ideas and values.

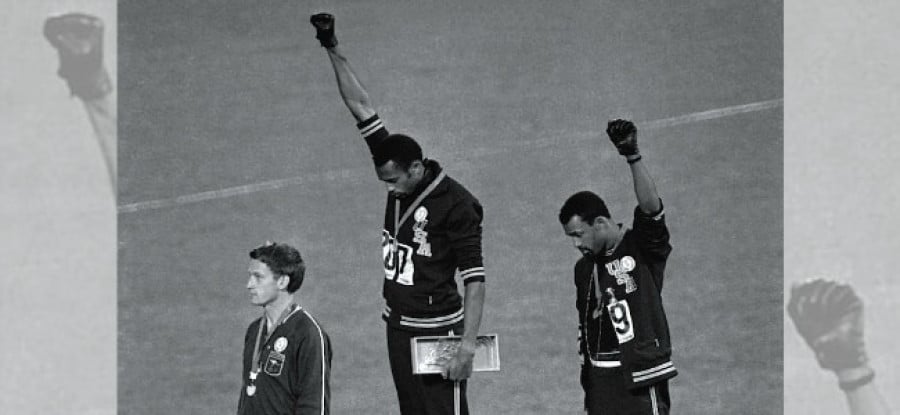

High-profile examples abound. To place this issue into context, consider Tommie Smith and John Carlos’ black-gloved stance1 against racial inequality in the 1968 Summer Olympics, or (momentarily stepping outside the football and Olympic spheres) members of the Zimbabwean cricket team wearing black armbands citing the “death of democracy in our beloved Zimbabwe”.2 Or, more recently, the “hands up, don’t shoot”3 gestures made by the St Louis Rams in their 2014 NFL game against the Oakland Raiders. In each case, these examples demonstrate the unique position that athletes occupy, especially given press coverage of major events.

Careful policing is required therefore to preserve value for official sponsors and to ensure that the focus of each event remains on sport rather than any other political, racial or cultural objective. Whether this is actually achieved in each case is a different question, but governing bodies have attempted to address these issues through enshrining certain overriding principles as core parts of the way events are staged and participants take part.

A clear challenge amongst all of this is to understand exactly what it is that these principles are designed to regulate. A ‘political statement’ is inherently subjective by its very nature and in most instances (as we will see) the relevant rules are wide enough to capture the more obvious demonstrable acts (e.g. those noted above) as well as the more subtle gestures of solidarity with a particular cause.4 In short, any statement of a non-sporting nature may well fall for consideration under the relevant rules, and the absence of a clear definition of what constitutes a ‘political statement’ brings an additional element of subjectivity into the interpretation of the rules themselves.

With 2016’s key sporting events in mind, this article compares the approach taken by FIFA, UEFA and the IOC in preventing athletes from making political statements in competition, and examines whether the approaches taken by each governing body are capable of consistent application.

FIFA – a ‘belt and braces’ approach

As if further confirmation was required, one need only type ‘FIFA’ and ‘politics’ into the nearest internet search engine to confirm that the two terms often appear in the same sentence. That the governance of football itself appears to be so political does nothing to alter this perception, and it is hard at times as an observer to see how FIFA can advocate that football remains apolitical when as an organisation these lines appear to be less clear.

From a player’s perspective, FIFA’s explicit rules on political statements in those matches and competitions falling under FIFA’s direct and indirect5 jurisdiction focus in particular on the display of messages on clothing. The FIFA Laws of the Game6 list, at Law 4, the basic compulsory equipment to be used by each player (comprising playing jersey, shorts, stockings, shinguards and footwear), which in turn is furthered by a decision of the International FA Board clarifying Law 4, which states that:

“the basic compulsory equipment must not have any political, religious or personal slogans, statements or images… The team of a player whose basic equipment has political, religious or personal slogans, statements or images will be sanctioned by the competition organiser or by FIFA.”

The same also applies to undergarments worn by players, and it is reasonably clear therefore that, as a player, wearing a political statement on your shirt or removing ones shirt or other item of clothing to reveal a statement underneath is going to land you in trouble with FIFA.

However, whilst FIFA is clear as to how officials should deal with these incidents during the course of a game and how cautions can be issued to players,7 what is more open-ended is the range of sanctions available to FIFA after the game. Here, the remit of the rules are widened from explicit reference to player clothing to include the full range of human behaviour, including political statements not simply confined to messages on clothing. These sanctions are found in the FIFA Disciplinary Code and are outcome-focused rather than prohibiting specific acts. For example, a player inciting violence or hatred (s.53), provoking the general public (s.54), carrying out offensive behaviour (s.57) or carrying out discriminative action (s.58) may well cover most forms of political statements within a game and all carry with them the threat of a fine for the player or, in some instances, lengthy bans.8 One example of this which readers may remember is Josep Simunic’s 10 game ban9 and CHF 30,000 fine for his pro-Nazi chants following Croatia’s World Cup qualifying play-off victory over Iceland in 2013.

The provisions of the FIFA Disciplinary Code echo the provisions of the FIFA Code of Ethics (e.g. s.23) and the eleven core principles set out at s.3 of the Code of Conduct more generally. From a legal perspective the various documents comprising the laws and regulations of FIFA should be viewed in conjunction with each other, rather than on a stand-alone basis.10 The net effect of this is that, in relation to political statements by players, through the interplay (and considerable overlap) between the various FIFA documents, FIFA gives itself some ability to mould its rules and regulations to the fact matrix before it in each case in order to achieve the desired outcome or sanction.11

A sensible approach (and heady luxury as a lawyer!) when one considers the many forms a political statement can take, but perhaps one that is unhelpful in achieving any form of consistent response. As with UEFA and the IOC (more of which below), FIFA’s response to political statements made by players is, by its nature, subjective. Some instances, such as the Argentinian team12 unfurling a banner in support of its country’s claims on the Falkland Islands have clear political motivation, however others, such as the Nicolas Anelka “quenelle” incident13 from 2013 require a judgement call as to underlying motivation.14 Whatever one’s view of these incidents, it becomes clear that because FIFA does not define what constitutes a ‘political’ slogan, statement or image (or indeed what constitutes offending ‘dignity or integrity’), FIFA is left to determine what it considers to be the actual nature of each statement. At the same time, defining these principles risks exclusion through artificial construct, and it is certainly a valid proposition to suggest that rules need to be capable of evolution to match the unpredictability of human behaviour. Either way, the rules as they stand rely on consistency of application from FIFA, and in some instances that has appeared to present a challenge.15

UEFA – more specific but still a subjective test

And what of UEFA? As the governing body for football at European level, for those matches and competitions organised by UEFA, the UEFA Statutes and related regulations will apply to any political statements made by players in any such context.16 Articles 1 and 2(a) of the UEFA Statutes make it clear that UEFA is:

“neutral, politically and religiously”, with an overriding objective to “promote football in Europe in a spirit of peace, understanding and fair play, without any discrimination on account of politics, gender, religion, race or any other reason”

These sentiments filter through into the detailed rules that apply to every match and competition organised by UEFA.

The UEFA Disciplinary Regulations17 contain an obligation on players to respect the FIFA Laws of the Game, and whilst the drafting is somewhat nebulous (note that the word ‘respect’ is used rather than ‘comply with’), it seems likely that the net effect of this wording would be to bind players in UEFA competitions to the applicable FIFA rules governing slogans on compulsory equipment noted above.

Whether this is actually needed or not (or ever tested in practice) is a moot point, especially as the UEFA Disciplinary Regulations go into further detail as to what constitutes a breach of the UEFA “principles of ethical conduct, loyalty, integrity and sportsmanship”, to which players must adhere. Specific breaches include “conduct [which] is insulting or otherwise violates the basic rules of decent conduct”18 and where a person “uses sporting events for manifestations of a non-sporting nature”,19 and these examples alone are likely to afford UEFA a right of direct action against players who make political statements during the course of a game or tournament.

To continue reading or watching login or register here

Already a member? Sign in

Get access to all of the expert analysis and commentary at LawInSport including articles, webinars, conference videos and podcast transcripts. Find out more here.

- Tags: Athlete Welfare | Brazil | Disciplinary | EUFA Disciplinary Regulations | Euro 2016 | Europe | FIFA | FIFA Code of Conduct | FIFA Code of Ethics | FIFA Disciplinary Code | FIFA Laws of the Game | Football | Governance | IOC | Olympic | Olympic Charter | Olympic Games Rio de Janeiro 2016 | Paralympic | Regulation | Russia | Sochi 2014 | UEFA | UEFA Statutes

Related Articles

- Why human rights law demands FIBA review its “no-turbans” decisions

- New guidance on how clubs should treat social media misconduct by footballers

- Navigating Olympic advertising: Rule 40 – a global perspective

- 10 articles that explain some of the legal considerations when using technology in sport

- How crowd disorder will be governed and policed at Euro 2016

Written by

Charles Maurice

Charlie is a senior associate at Stevens & Bolton LLP and specialises in the sports, media and entertainment sectors. Charlie advises on a wide range of sporting issues and has particular experience in the motor racing and football industries.

Global Summit 2024

Global Summit 2024